Microfluidics innovator Dr. Yiheng Qin honed his skills by training at world-leading facilities under leading investigators. But his inspiration for breakthrough sensing technologies includes old-school technologies such as ink and the humble lead pencil.

His marriage of high-tech expertise with these low-tech materials resulted in a simple, low-cost solution to a global problem: how do resource-limited communities know their water is safe to drink?

“I was interested in microfluidics from my undergraduate days because the applications are so huge,” he says. “It can be used for sensing, and various kinds of chemical and biological uses.”

That interest led him to Sweden’s Chalmers Institute of Technology, where his Master’s studies focused on flexible electronics. “They have a very, very advanced cleanroom and I used the facilities there to fabricate tiny, fine structures,” he says.

He expanded on this experience at McMaster University, pursuing his PhD under Dr. Jamal Deen, Canada’s Research Chair in Information Technology, and Dr. Nan-Xing Hu, a Research Fellow at Xerox Research Centre of Canada. It also gave him the opportunity to take part in a collaborative Canada-India project, looking at rapid, reliable water monitoring in areas with no expensive equipment or water quality technicians.

‘Industries are interested in using our techniques in their own products’

Qin was intrigued by this challenge, and inkjet printing seemed a possible solution. “I thought, we could use this controllable medium to create a sensor for the acidity of water, which is a key indicator of water quality.”

He did this by developing a novel printing process to deposit a thin layer of palladium. Unlike conventional manufacturing, inkjet printing means only the areas needed for sensing receive the palladium ‘ink’, meaning very little metal consumption, eliminating waste and reducing costs.

Qin then began experimenting with even simpler approaches: hand-drawing sensors on paper, using low-cost materials such as paper, pen and ink, or a graphite pencil, for other water quality indicators such as free chlorine. These straightforward, sustainable processes mean users and manufacturers don’t need to be trained technicians – a major advantage for remote communities without access or funds for expensive analytical expertise or equipment.

Next, he integrated his pH, temperature, and free chlorine sensors into a single electrochemical sensor probe—for a total manufacturing cost of less than $0.50. “You dip the sensor probe into the water and a cable connects it to an electronic system that gives you a reading.” He successfully tested the system with water samples from Lake Ontario and multiple municipal water supply systems. Testing showed the sensor to be more than 90 percent accurate.

The versatility and commercial potential of his work has attracted a number of industrial collaborators, including Xerox Canada, Voltek Energy Inc., KIK Custom Products Inc., and biomedical giant ChroMedX Ltd. “Industries are interested in using our techniques in their own products,” he says. Currently he’s working ExVivo Labs Inc. of Kitchener, ON, where he is doing product development for allergy testing devices.

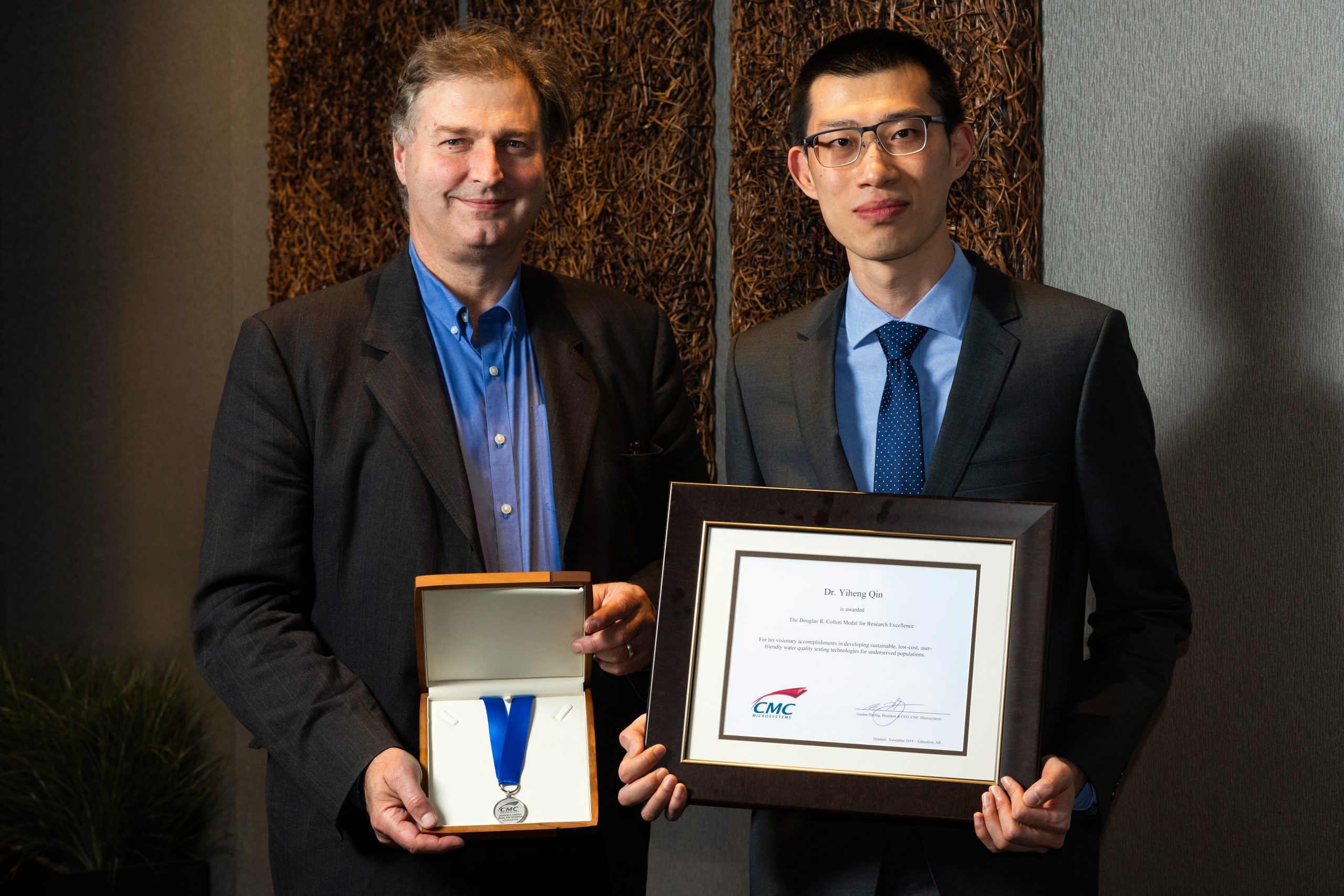

In 2019 Qin was awarded CMC Microsystems’ Douglas R. Colton Medal for Research Excellence in recognition of the novelty and impact of his work. But for him the biggest reward has been fulfilling his own goal of addressing a longstanding need. “Many communities have been under boil water advisories for years. Now I know it’s possible to make something simple and useful so that people can know their water is safe to drink.”

March 2020