For many farmers today, cultivating crops is a high-tech exercise combining satellite data, precisely calibrated guidance systems, and a great deal of information processing power. In fact, innovation regularly makes new inroads in agriculture, as Western University’s Jayshri Sabarinathan has seen for herself.

“Until I got into this, I did not recognize how much sensing and data have revolutionized the industry, both in the greenhouse and in the fields,” she says. Now she is working with a Canadian company to make crop-based data collecting even more effective.

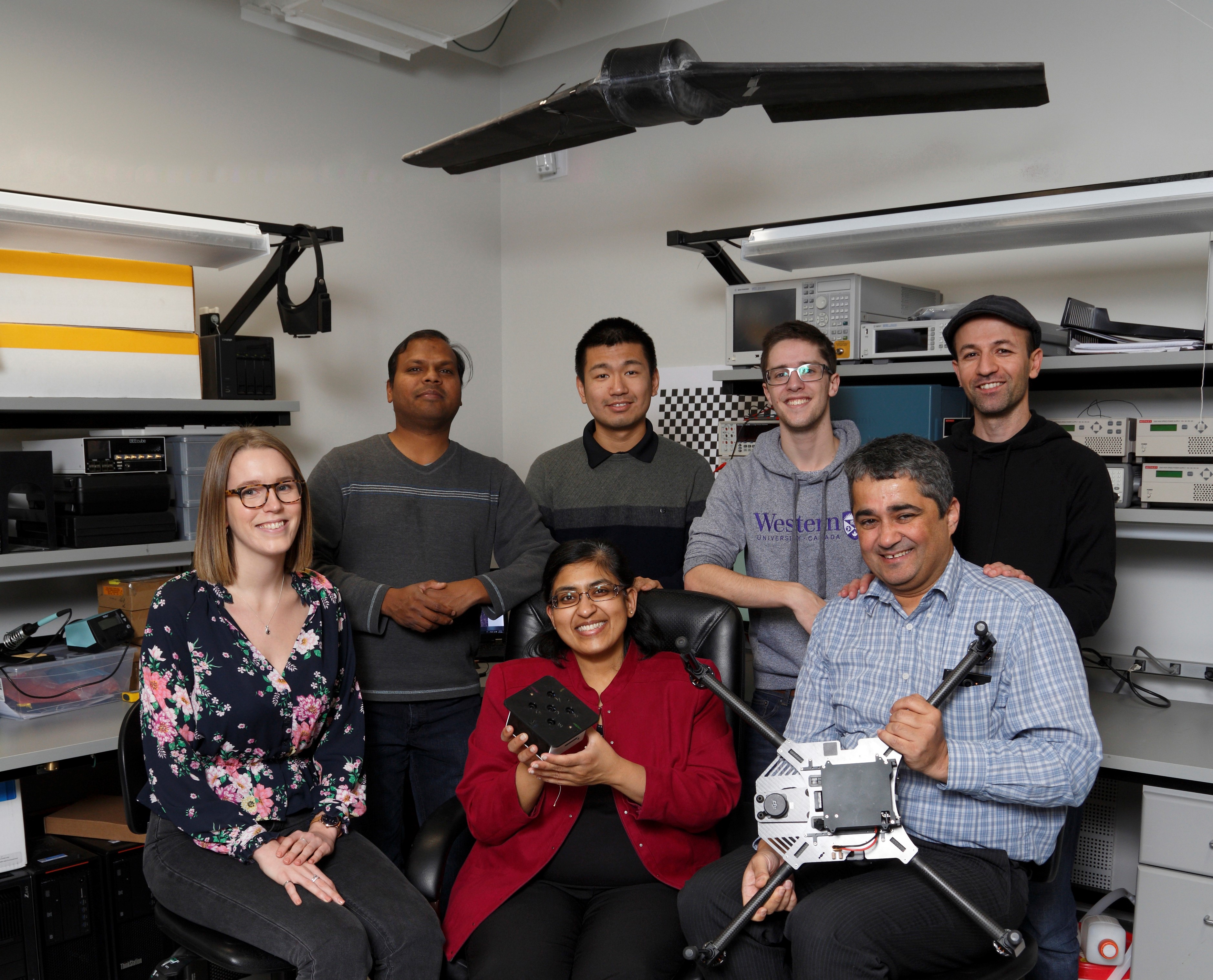

Sabarinathan, associate professor in the Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering with experience in microsensors and nanofabrication, has found an unlikely niche within this revolution: enhancing the capabilities of multi-spectral cameras used to monitor crops. More specifically, she has been increasing the wavelength bands captured by such cameras, which in turn increases the type of data they can collect.

That data can include details such as the onset of disease or changes in the rate of nutrient uptake by plants. This real-time feedback can determine inputs such as how and when to deliver pesticides or fertilizers. That response can be especially crucial in greenhouse settings, where problems can emerge over a matter of hours. In southwestern Ontario, where such indoor operations may cover dozens of hectares, a monitoring failure can be catastrophic.

“The manufacturer wants a camera with the ability to tailor these particular wavelengths to the requirements of their clients, and with features that will allow them to gather and process this information and then tell the farmers what’s going on in their fields,” she explains. “What you want is information from a range of wavelengths, all the way from the visible to infrared. But that’s a lot of data and generally requires heavier instruments.”

Weight matters because these cameras are carried by small robots or borne aloft on drones as a highly efficient way of surveying the state of a farm or greenhouse. Such cameras are already commercially available, but A&L Canada Laboratories, a London, Ontario company that works extensively with this equipment, approached Sabarinathan to investigate ways of enhancing these hard-working technologies.

“This collaboration enabled us to draw on the expertise needed to advance our R&D in environmental monitoring,” says Greg Patterson, CEO, A&L Canada. “The results have been very valuable to us.”

“A&L does everything from the ground up, and they wanted a camera that was not just portable but covered more of the wavelengths that interested them with better spectral accuracy,” Sabarinathan says. She is looking at outfitting drones capable of taking in at least seven and possibly more bands, as well as offering customizable filters and adjustable resolution.

“By moving to a platform similar to what you find on your smartphone, we’re hoping this instrument will be twice as fast as the multispectral cameras currently on the market,” she says.

This work has been supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) and the Ontario Centres of Excellence (OCE).

‘This kind of monitoring of environmental factors and stressors has become fundamental’.Sabarinathan is grateful to CMC Microsystems for providing her with access to software and testing tools that accelerate everything from initial design to final review of prototype performance. “CMC really offers the infrastructure for us to be able to develop these sensors,” she says.

Her ability to conduct this work has also allowed her to collaborate with remote sensing experts Dr. Brigitte Leblon at University of New Brunswick and Dr. Jinfei Wang in Western’s Department of Geography, as well as autonomous robotics expert Dr. Ken McIsaac in Western’s Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering. She is looking forward to systems that are almost autonomous, which will further improve their value not just to farmers but to the ultimate clients — consumers.

“Field users want to get this data on their computers as quickly as possible, then send it to a company like A&L for further processing,” she says. “In an intense agricultural setting like southwestern Ontario, this kind of monitoring of environmental factors and stressors has become fundamental.”

Photo: Steve Martin/Photo Features

February 2019